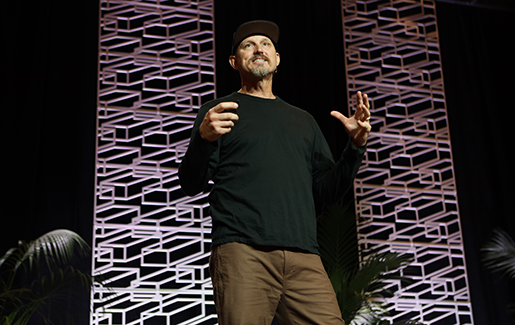

.png?sfvrsn=94790fef_2) Mick Ebeling didn’t set out to build a device that would later win TIME Magazine’s Invention of the Year in 2010. He just wanted to give one Los Angeles artist with ALS the ability to draw again. He didn’t set out to try and give patients with Parkinson’s disease more control over motor functions, he built sensory devices that could let deaf people enjoy live concerts—it just so happens they might also help the first group too. In each case, he took an idea that seemed far-fetched or unreal and made it happen.

Mick Ebeling didn’t set out to build a device that would later win TIME Magazine’s Invention of the Year in 2010. He just wanted to give one Los Angeles artist with ALS the ability to draw again. He didn’t set out to try and give patients with Parkinson’s disease more control over motor functions, he built sensory devices that could let deaf people enjoy live concerts—it just so happens they might also help the first group too. In each case, he took an idea that seemed far-fetched or unreal and made it happen.

Ebeling, the CEO of Not Impossible Labs, has built a reputation and a career for doing things that nobody thought could be done. He won TIME Magazine’s Top Invention award a second time in 2021 (the only person to do so) for an app that allows food-insecure individuals to discretely pick up no-cost meals from participating restaurants.

“We have 50 million Americans who are food insecure, who struggle daily to put food on the table. We have to look at the supply chain of food, where more food goes to waste than we consume. What if we created a better supply chain?” Ebeling said during a keynote session at ChannelCon 2023 in Las Vegas.

Not Impossible Labs developed APIs that integrate into a number of disparate food sources, from restaurants to grocery stores to food shelters, and built Bento, a messaging app that allows someone to request a food order (even with dietary or other restrictions) and pick it up for free, no questions asked.

“You walk in with dignity, you walk out with dignity and a meal,” Ebeling said.

MORE: Read CompTIA’s Q&A with Mick Ebeling

Every Innovation Started as an Impossibility

Every invention in history started out as an idea that people thought couldn’t be done, Ebeling said.

Every invention in history started out as an idea that people thought couldn’t be done, Ebeling said.

“Name something that is possible today: What you’re drinking out of right now, the computers you’re on, lights, chairs, whatever. Every single thing that is possible today was impossible before it was possible. Someone said, ‘I’m tired of sitting on rocks, I gotta build a chair.’ When you are encountering something that’s hard, difficult—and we do that every day—it’s ok to say it’s hard. Just don’t say the ‘I-word.’ You get in more trouble in my world for saying the I-word than the F-bomb,” he said.

An invention or a breakthrough may not happen this year, this decade or while you’re alive, but once people start to say ‘this is really hard, but it’s not impossible’ that’s when they start to see what might happen, Ebeling said. “That changes our entire mindset on how we attack problems. Impossible is a fallacy, a temporary state of being.”

Embracing ‘Technology for the Sake of Humanity’

Not Impossible Labs’ mission statement is “Technology for the sake of humanity,” Ebeling said.

“It’s about how to create technology to solve a problem. It doesn’t have to be new technology but it’s about how to get it to as many people as possible. Everything is based on impact.”

He helped create a 3D-printing operation for prosthetics in Sudan where limb loss is an all-too-frequent occurrence due to regular bombing. Other projects underway for Not Impossible Labs are finding a way for the blind be active in action sports and a landmine identification and deactivation program in Ukraine.

“Why do we pull this stuff off? It’s because we shouldn’t. We don’t have degrees, diplomas, credentials. We focus on what I call beautiful, limitless naivete,” Ebeling said.

Ebeling challenged ChannelCon attendees to find a way to find their not-impossible mindset too.

“What’s the story you’re going to tell with your life? How many of you woke up today with no place to eat, no place to stay or if you got sick you couldn’t see a doctor? We’re the lucky ones. Ok, great. How are you going to use the blessings of your life? Everyone is going to go back to their lives, Zoom calls, soccer practices. But what if everybody in this room just decided to help one person,” he said. “There’s 1,000 people here. If 1,000 people go home and do that, it’s not 1,000 people that get helped. We can create exponential change by simple, simple actions.”

Getting people to believe that nothing isn’t possible isn’t hard, because people already have it in their head, even if it’s buried deep, Ebeling said.

“Ultimately, I don’t see my job here as to inspire you, I’m here to remind you that you have the potential to do it anyway. We somehow forget this,” he said. “When we have a project, most are volunteer teams and people crave having that ability. It provides this release of energy. People want to have purpose in their life.”

Add CompTIA to your favorite RSS reader

Add CompTIA to your favorite RSS reader