Introduction

Ask any CEO or business executive about what keeps them up at night, and “cybersecurity” is almost certainly near the top of the list. Ask those same people what they are doing to improve their cybersecurity posture, and the answers will likely be all over the place. There might even be blank stares. The truth is that cybersecurity has been top of mind in recent years, especially after the shifts to strategic IT in the cloud and mobile era; however, making a similar shift toward a modern cybersecurity approach has been more challenging.

Soon after cloud adoption became mainstream, it became common knowledge that the traditional secure perimeter was no longer sufficient. For decades, companies had been focusing their cybersecurity efforts on building the best wall possible around their digital assets, which were almost exclusively located in defined office settings. Migrating systems to cloud providers and allowing access from mobile devices completely changed the nature of digital workflow, all while a broader adoption of technology led to more tantalizing prospects for cyber criminals.

New tactics came into play to reflect the new landscape. Companies started investing more in data loss prevention (DLP) as a way to handle more fluid data patterns. Workforce education took a step forward as more employees were using more devices and systems. These tactics, though, felt like a growing collection of individual practices. There was no overarching philosophy that fully tied everything together. Zero trust has emerged as the modern approach to cybersecurity that drives each specific action. The basic premise is that no part of an IT system should be trusted implicitly, whether that is network traffic from what appears to be a known location or a user access request with a single credential. Extra steps must be taken to verify, and new questions must be asked to conduct digital operations. The basic premise of zero trust is simple, but the implications are far-reaching. Embracing a zero trust approach will not happen overnight. The adoption process starts with education around zero trust principles, then moves into analysis of the investment needed, finally culminating in development of process and skills.

ZERO TRUST PRINCIPLES

The main thing to understand about a zero trust framework – and the thing that makes adoption so difficult – is that zero trust is not a single product or action. More than anything, zero trust is a philosophy around cybersecurity that informs questions and decisions. To embrace a zero trust philosophy, business executives must understand three key differences between zero trust and a traditional view of cybersecurity:

- Internal vs. external: Previous cybersecurity efforts were focused on events outside the company, primarily the cyberattacks that required a strong defense. A zero trust approach recognizes that cybersecurity is driven just as much by internal events, such as the use of cloud systems or the implementation of smart devices.

- Process vs. product: While certain cybersecurity tools will be added within a zero trust approach, zero trust is far less product-centric than the secure perimeter, which relied heavily on firewall and antivirus to provide protection. Products in the zero trust framework are largely in service of business processes that validate proper behavior.

- Business vs. technical: For many organizations, cybersecurity has been just one part of overall IT activities. As such, it was viewed as a technical problem. Today, cybersecurity is a business imperative, and organizations are cultivating cybersecurity chains with representatives from every functional area to ensure that cybersecurity factors into overall business operations.

With a grasp of high-level concepts, organizations can begin moving toward specific components of a zero trust approach. Many organizations, including the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), have built resources mapping zero trust principles to specific steps. In these early days of adoption, the exact terminology may differ, but several best practices are emerging.

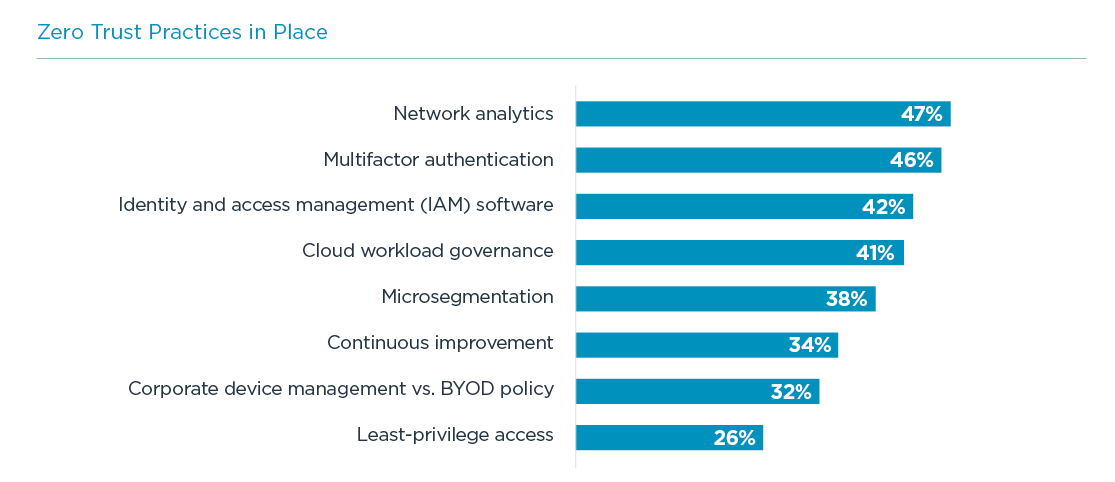

Network analytics is certainly a practice many organizations had in place before considering zero trust, but it is also a key component of the evolving philosophy. It is no longer sufficient to assume that security breaches are blatantly obvious. Many breaches can remain undetected for a long time, and network analytics provide ongoing monitoring for any suspicious traffic that could indicate an intrusion.

Multifactor authentication (MFA) has become the primary tool in performing user validation. Whether it is through codes sent via text, the use of third-party apps or biometrics, an additional layer of verification beyond passwords significantly reduces unauthorized access. MFA is not bulletproof, but it addresses one of the most common vulnerabilities – a 2021 Verizon Data Breach Investigations. Report found that 61% of breaches in 2020 were executed using unauthorized credentials. Identity and access management (IAM) software provides yet another layer in solving this critical issue.

As organizations move more and more resources to cloud systems, cloud governance grows more and more critical. One of the primary benefits of cloud systems is ease of use, but this benefit can turn into a liability as cloud infrastructure or software is quickly spun up and then left unattended. In addition to keeping costs in check, cloud governance helps trim unused resources so that they do not become unwatched entry points for cyber attacks.

The final practice to highlight is microsegmentation. Many organizations already have virtual networks in place to better control network quality for different applications. Microsegmentation is an evolution of this trend, using software to divide a physical network into multiple zones for separate applications or even specific workloads. The granularity of the network depends on the availability of network administrators, but well-defined zones can limit the attack surface of the overall network and provide greater capability for containing breaches.

The mix of technical tactics and organizational processes makes it clear that many discrete tools and practices can be part of a zero trust approach. Furthermore, it is simpler for organizations to consider individual components rather than treating zero trust as a singular endeavor. The best way to adopt zero trust is not to define a set of criteria that indicate complete success, but to build a road map identifying the best steps to take based on the needs of the organization.

THE FINANCIAL SIDE OF ZERO TRUST

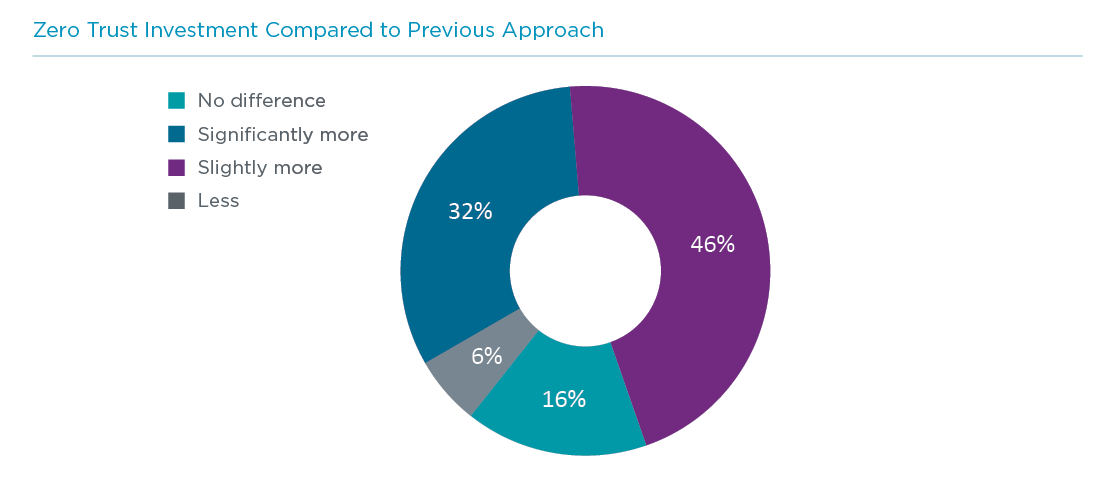

Unfortunately, the multifaceted nature of zero trust comes with a cost. CompTIA’s recent State of Cybersecurity research finds that 78% of companies that have implemented a zero trust approach see a jump in investment when compared to their previous cybersecurity strategy. It should be noted, though, that zero trust is not necessarily the villain in this situation. Even before zero trust was recognized as the driving force for modern cybersecurity, companies were beginning to increase cybersecurity investments thanks to the growing complexity of digital operations. Zero trust simply gave a liable to the phenomenon.

Taking things a step further, cybersecurity is not even the sole culprit when it comes to growing budgets. While headlines occasionally report shrinking IT budgets, those stories are often focused on the budget for the IT department itself. At the organizational level, overall technology budgets are typically growing, with new spending often coming from business units such as marketing or finance. Even IT departments may find that their budgets are growing as the organization recognizes that IT is no longer a cost center and strategic investment is needed for digital transformation.

More investment, especially within a strategic context, leads to an expectation for more metrics. The traditional metric around cybersecurity has been whether or not the organization has experienced a breach or other cybersecurity incident. In an environment with greater reliance on digital data and broader use of technology tools, security professionals need to build a stronger case around proactively reducing risk and anticipating incident response effort.

Building the case starts with reframing cybersecurity in the context of modern digital operations. During the secure perimeter era of cybersecurity, the function was viewed as one of many IT responsibilities, a part of the overall technical plumbing that was needed for business units to deliver results. The critical role of technology in today’s workflow along with the increased appeal of cybercrime for financial or political gains has changed the function of cybersecurity. Rather than being an offshoot of IT, it is a critical business function, on par with financial management or legal oversight. If cybersecurity is viewed as a critical function, the next step is establishing the proper financial mindset. Obviously cybersecurity is not a revenue-producing activity, but neither are finance or legal. At the same time, finance and legal are not exactly viewed as cost centers; businesses are constantly trying to trim costs in those areas but instead make investments as needed in order to add specialized skills or provide better service Cybersecurity should also not be treated as a tax or straightforward cost of doing business. The appropriate viewpoint is somewhere in the middle, where a traditional return on investment calculation does not perfectly apply but here is till some expectation around quantifying success beyond a simple binary measurement. Two components of the zero trust approach address this need for measuring success. First, risk analysis should be a more rigorous activity. A secure perimeter did not demand detailed risk analysis since everything important was simply placed behind the firewall. A more granular cybersecurity approach requires a more granular understanding of risk, including the importance of each component and the potential costs involved if components are compromised.

Second, risk analysis, along with mitigation plans and preventive steps, should be constantly reviewed and modified. The digital landscape is constantly changing, so solutions cannot be static. Building an ongoing process for analysis and improvement is part of the zero trust mindset.

With those overarching policies in place, detailed metrics can be defined to demonstrate effectiveness. In the early days of zero trust adoption, best practices around metrics are still being defined, but some examples include the number of systems with up-to-date patches, the percentage of the workforce with current cybersecurity awareness training or the amount of network traffic analyzed for suspicious behavior. Whatever the metrics are, they should reflect the consensus viewpoint around how cybersecurity helps the business achieve its strategic objectives.

REFINING SKILLS FOR ZERO TRUST

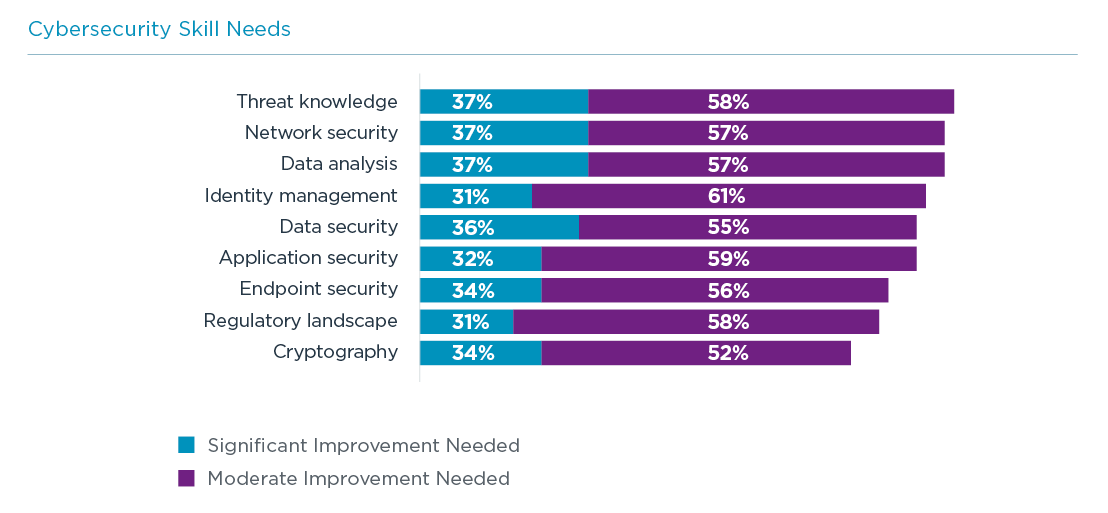

Given the scope of change in the overall approach to cybersecurity, business executives might expect there to be drastic skills gaps as they move toward a zero trust framework within the organization. In reality, the picture is not quite so alarming. The good news is that zero trust alone does not drive new skills. Much like the investment situation, the skills needed to implement a zero trust approach are largely the same skills that have been needed over the past decade as companies have considered a range of new cybersecurity initiatives. The challenge is that there is still a steep curve for most firms in finding and developing these skills.

Skill development shares many traits with other shifts in cybersecurity. Just as the complexity of the cybersecurity ecosystem forces cybersecurity to be a separate business function, the same complexity drives a need for specialization. Companies not only have to separate cybersecurity from broader IT activity but also have to consider building specialists rather than cybersecurity generalists.

At a high level, specialization is needed because a large portion of cybersecurity work is technical in nature and a large portion is not technical. Non-technical areas include risk management, regulatory compliance or privacy. Many of these areas are process-driven and have minimal overlap with cybersecurity architecture.

The technical side, though, is the side that companies are most familiar with and most likely to prioritize. The high focus on cybersecurity exacerbates the supply/demand problem already found in the larger technology workforce. Accelerations in both demand and complexity have created a situation where companies are seeking more expertise than the market can readily supply, and businesses are exploring alternative solutions to traditional talent pipelines.

The first step in any new solution is building an understanding of the exact skills that are needed. Another way to think about specialization is to recognize a high degree of variability in job roles. In the past, it may have been sufficient to hire a security engineer to serve the organization’s needs. Today, one security engineer may have a markedly different skill set than another.

Businesses need to know which skills are needed for modern security, then assess the kills currently on board. In some cases, there may be a complete lack of skill. For example, a medium-sized firm may not have any skills in the area of application security. In most cases, though, the problem is one of degree. The same firm may already have security specialists or other IT workers with network security skills, but those skills need to be improved.

After performing an assessment and identifying the areas where improvement is needed, the real work begins. Finding skills on the open market is not easy or cheap. Especially as companies seek out more advanced skills, they are fighting over a small pool of candidates.

One of the most popular solutions is training and certification. Rather than crossing fingers and hoping to land the perfect cybersecurity expert, companies are investing in their existing workforce. In doing so, they find multiple benefits.

First, companies are able to target exactly the skills they need. In situations where existing skills need to grow or new skills need to be added in a very specific way, organizations can customize training to their exact specifications. New headcount can be reserved for more strategic roles such as security architect or security operations center (SOC) manager.

Second, the entire workforce can be considered for filling skill gaps. Where skills might overlap between technology and business process, individuals from business units may be candidates for training. These individuals already understand the corporate culture and internal workflow, so there is no cost in acclimating a professional new to the company. Finally, investment in skills is a key part of workforce retention. The supply/ demand constraints make it difficult to hire, but they also create potential churn as employees seek greener pastures. Moving to a zero trust framework creates many new opportunities, and helping existing employees take advantage of those opportunities can build loyalty leading to long-term success.

Read more about Cybersecurity.